In this photograph we see Olaudah Equiano. I had never heard of Olaudah Equiano, but he is monumentally important in the history of slavery. Here we see a man dressed in the typical garb of the eighteenth century gentleman. Looking closely you can see he is dark skinned. He appears to be brooding in a desolate Arctic landscape.

Equiano wrote an autobiography The Interesting Life of Olaudah Equiano, 530 pages 2 volumes, published in 1789. It describes his personal experience growing up in Nigeria, being captured by slavers when he was eight, surviving the Middle Passage to Virginia, then escaping to London and the West Indies, but finally buying his freedom in 1766. He then went to Central and North America, the Mediterranean and the North Pole on an expedition “to collect zoological specimens and record whale and polar bear killings. He settled in London and married an English woman, becoming a leader in the fight against slavery. He overturned the cliché of Africa as a place of barbarism, and describes instead his home as “idyllic with strong leaders, varied foods and festivals, and defined sense of order.”

This memory is contrasted with vivid descriptions of “slave traders as cruel and barbaric; of suffocating sweat, smells and traumas on ships crossing the Atlantic and the humiliations he endured and witnessed in the slave trade around the world. ” Equiano led the abolition movement in England and his autobiography is said to have contributed to the success in abolishing slavery in England and the British Colonies (although not the huge financial benefits of the trade). He appears in the movie Amazing Grace that mainly focuses on the British leader of the abolition cause 18th-century England, House of Commons member William Wilberforce. Olaudah Equiano ‘s story would make an excellent movie in itself. In the photograph above, we see him brooding in a Tundra landscape, with glaciated peaks in the background, a perfect image for our world today.

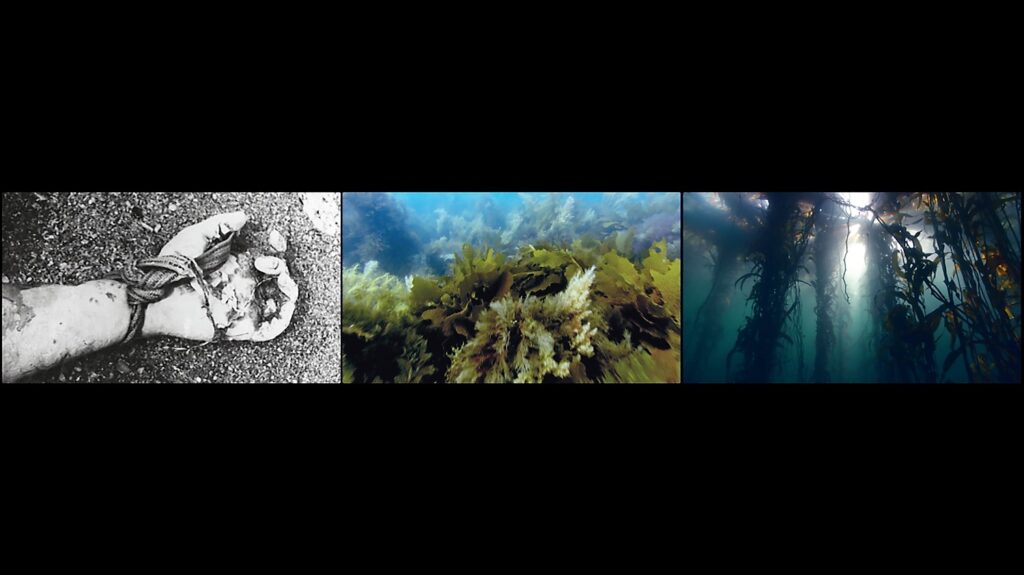

Projected as three large adjacent images, Vertigo Sea overwhelms us. Sometimes the images flow from one to another, other times they sharply clash. If you have ever seen one of David Attenborough’s BBC nature films, you will recognize some of his incredible footage: the artist gained permission to use it after befriending Attenborough for a full year. But Akomfrah goes the extra step that Attenborough only touches on in his earlier films although his most recent film A Life on Our Planet is all about the climate crises caused by our own actions. Here is a trailer for it

Akomfrah juxtaposes stunning nature sequences with the murder of humans in the slave trade and the hunting of whales as well as posed images of detritus by the sea and including dead animals..

In the whale hunting scenes, from historic footage, we watch horrified as the spears enter the animal and the helpless whale bleeds into the sea and dies, even as another screen celebrates their beauty.

In an extraordinary juxtaposition we gasp in disbelief at the reenactment of slaves forced overboard alive. Akomfrah gives us the unrelenting brutalities of genocide by hunters of animals and people who shared a single minded goal – to make money.

Interspersed in the film are many quotes. What stands out are excerpts from Heathcote Williams’s 1988 poem Whale Nation. The book evokes the whale in all its aspects for the first 50 pages, then our relentless pursuit of it for its oil, its baleen, its teeth, its bone and finally a literary survey of references to the whale.

“From space, the planet is blue/ From space the planet is the territory/Not of humans/ but of the whale.”

Heathcote Williams book combines a celebration of the whale, stunning photographs of whales that partner with different verses of his long odelike poem, a celebration of native respect for the whale by the Kwakiutl and Nootka.

then a rapid shift to “But other men have elected to view the whale as an essential component of an expanding economy.”

As in Akomfrah’s film we see images of men on whalers targeting whales first with a harpoon, then a grenade. As Williams describes it “four barbed flanges pivot on hinges/, and as the whale struggles,/ the strain on the rope snaps the barbs open: /they fly out ripping into the lungs and inner organs/ embedding the harpoon inside the whale, anchoring her body.

“And it goes on from there in gruesome detail and with photographs. “Yet civilization has been built on the back of the whale. Coastal settlements followed the presence of whales;/Shore stations near the whaling grounds became cities.” ( he lists 35 cities) then lists the products that come from whales, first of all oil “urban conglomerates plugged into the corpse of the whale, growing larger and larger by its light./

The whale’s insulating wet suits backed off in flensing ships in untold billions for fuel/ for lamps/and candlewax/ for whale oil appliances for sweat shops and factories, for domestic lighting, for street lighting for shop lighting. For flexible baleen filaments for watch-springs, umbrellas, toys and upholstery, even the springs in the first typewriter. Millions and millions and millions died in a marine holocaust generating the implacable human appetite for electricity, petroleum and plastic. For soap, for margarine, for lipstick, for detergents, for brushes and brooms; for linoleum; for medical trusses. On and on the list goes for pages, but then in the end he returns to the whale itself”

From space, the planet is blue

From space, the planet is the territory

Not of humans, but of the whale.

The second half of the book includes quotes about the whale over centuries. What stands out above all is the whale’s intelligence, and its superiority to humans in so many respects, particularly in that it does not experience greed, it does not have any need to find shelter. It spends its time playing.

Within Vertigo Akomfrah has also embedded quotes from Moby Dick, the quintessential whale story.

Occasionally the sequences of Vertigo Sea take a breath with three blank blue screens. But you will not be able to stop watching.

Akomfrah speaks of the flux and fluidity of water as suggesting the past, present and future. Our bodies are 85 percent water. But rather than acknowledge our connection to the sea, the planet, and its occupants, he stated, our hyper consumerism is destroying it.

By connecting the hunters of the sea to the hunters of humans, Akomfrah lays bare the essential brutality of the so called “englightenment” era, as well as the connection to our present world. Today, especially in the Northwest, we are looking at the dying out of Orcas as a result of lack of salmon, the dying of salmon as a result of dams, the dying of wildlife as a result of oil exploration and the destruction of habitat, the extinction of keystone species, as a result of ignorance, greed, and stupidity.

We are also seeing the continuing brutality to the black race and other people not deemed important is our prison system, our detention system and our police killings in the street.

Brutalities and consumerist greed still is destroying human life, the natural world and the interconnections between them. I end with a quote from the brilliant ( one might almost say clairvoyent) Octavia Butler who is featured in another Akomfrah film, the Angel of History, about Afro futurism.